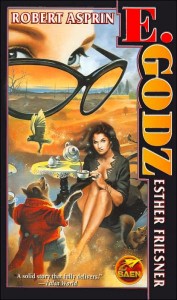

Meet Edwina Godz, CEO of E. Godz, Inc., America’s largest and only family-owned clearinghouse for magical power. She’s got a small problem. Two of them, really: her children, vapid Peez (the Dateless Wonder, and Emergency Virgin for several New York magical groups) and vacuous Dov (with a smile for every occasion). Not only do they hate each other to the point of absolute detestation, but it’s a sure bet that if they take over the company when Edwina dies, they’ll tear it apart in their ensuing power struggles, ruining everything Edwina has worked so hard to build. Her solution? Die early, and make the two fight it out, with only one sibling coming away with complete control of the company. So she sends out her letters, climbs into bed, and waits to see what’ll happen, and who’ll emerge on top, kicking and screaming.

Meet Edwina Godz, CEO of E. Godz, Inc., America’s largest and only family-owned clearinghouse for magical power. She’s got a small problem. Two of them, really: her children, vapid Peez (the Dateless Wonder, and Emergency Virgin for several New York magical groups) and vacuous Dov (with a smile for every occasion). Not only do they hate each other to the point of absolute detestation, but it’s a sure bet that if they take over the company when Edwina dies, they’ll tear it apart in their ensuing power struggles, ruining everything Edwina has worked so hard to build. Her solution? Die early, and make the two fight it out, with only one sibling coming away with complete control of the company. So she sends out her letters, climbs into bed, and waits to see what’ll happen, and who’ll emerge on top, kicking and screaming.

Now it’s up to Peez and Dov (and yes, I wince at the names also) to make the rounds of E. Godz’s biggest subsidiaries, to gladhand and schmooze and build their power bases. Winner takes all. Dov, accompanied by a particularly persistent talking amulet, and Peez, accompanied by her overly manipulative magical teddy bear Teddy Tumtum (stop rolling your eyes) are on the road and in the boardroom. And so each of them visits the representatives of the groups that power E. Godz.

There’s the Native American shaman who’ll give anyone a spirit quest for $3,000 a pop (only the most glamourous of spirit totems given, of course). There’s the Egyptian death cult in Chicago that never grew out of the frat mentality. There’s the voodoo dude down in New Orleans, the Wiccan high priestess in Salem, the Eskimo who’ll make a totem pole of any pantheon you want to worship, from talk show hosts to sports team mascots to actual totemic animals, and finally, there’s the Reverend Everything in L.A., who puts on a show no worshipper is soon to forget. As Peez and Dov visit each one, they learn more about the ways of the business, and the relationship of magic to belief to profit. And if they learn a little more about themselves in the process, so be it.

The big question is, what happens when they’re done, and it’s time to take the fight right on back to dear sweet dying mother Edwina herself? The fur will fly, secrets will be revealed, and the big question of who’ll get the family business will finally be revealed.

To be honest, I’m really not sure what to make of E. Godz. The name is a horrible pun of sorts, and I kept expecting some sort of online diety subscription service (hmmmm, idea….). Esther Friesner is superb with the comic fantasy and sly humor, though subtlety isn’t always her strongest point when she’s going for the funny.

Robert Aspirin has always been hit and miss with me, his Myth-Adventure books clever and entertaining, but not exactly what I’d consider deep thought. Together, the result was bound to either be very good or a little muddled, and I fear E. Godz is a little muddled, as though Aspirin’s and Friesner’s styles didn’t entirely mesh. True, there were laugh-out-loud amusing parts, and I kept disturbing my wife just to read selected bits to her. True, it’s an entertaining and interesting read. It wasn’t until I was done that I was able to look back and see a deeper, more intriguing and more philosophical message running throughout the book, regarding the relationship of faith with the need to believe in something. Occasionally heavy-handed, the message still flew under the radar in a subtle way, surprising me with its introspective nature. The mixture of satire and commentary is well-handled, though it could have been more polished.

Unfortunately, no message can make up for saddling the protagonists with the names Peez and Dov. That’s just painful, especially for a book taking place in a contemporary American setting.

On the whole, I really did enjoy E. Godz, but it’s not about to supplant any of the Myth-Adventure books as a standout Aspirin novel, nor will it replace Druid’s Blood as my favorite Esther Friesner book. My honest advice is that it’s worth checking out, but not one to immediately race out and buy in hardcover if you’re on a budget.