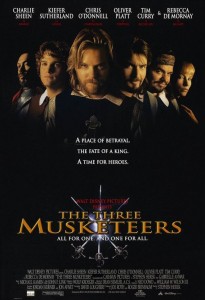

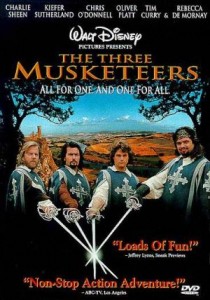

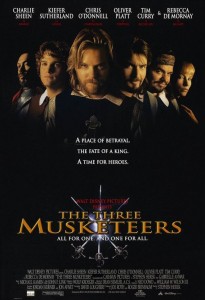

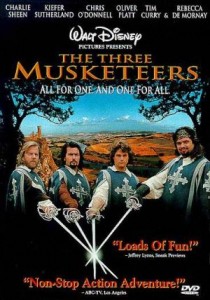

We all have those perfect films, the ones in which everything comes together, the story shines, the characters click, and the entire movie is resonate. That rare movie you can watch unlimited times, and keep going back for more. Where nothing disappoints, and everything excites. Forget what the critics say, forget what your friends say, forget everything but that, for you, this movie is damned near perfect. We all have those pantheons in our heads. And for me, the 1993 Disney version of The Three Musketeers ranks right up there as one of my all-time favorites.

We all have those perfect films, the ones in which everything comes together, the story shines, the characters click, and the entire movie is resonate. That rare movie you can watch unlimited times, and keep going back for more. Where nothing disappoints, and everything excites. Forget what the critics say, forget what your friends say, forget everything but that, for you, this movie is damned near perfect. We all have those pantheons in our heads. And for me, the 1993 Disney version of The Three Musketeers ranks right up there as one of my all-time favorites.

I’ve never read the novel by Alexandre Dumas. Lord knows I’ve tried but, to be honest, epic French fiction just isn’t my thing at all. I prefer what others make of the stories far more than I do the originals. I like the concepts, the themes, the nature of the stories. I enjoy stories told on such broad, sweeping levels with such multi-layered, three-dimensional strokes. I enjoy Les Miserables. I greatly enjoyed the recent Count of Monte Cristo remake. And I hold The Three Musketeers up as an example of how to do something right.

I understand that they took more than a few liberties in trying to compress the original French paperweight into a feature-length film. How many subplots, characters, and themes must have been cast by the wayside? What language was ripped to shreds or replaced entirely? How could anyone hope to stay absolutely true to the original text? Well, as I said to those who doubted The Lord of the Rings: Fellowship of the Ring, “Accept change.” Accept that what they did for this movie was to take the book, the very essence of the story, and distill it down into its barest, most profound nature, and start fresh.

The basic storyline is, at its root, simple: The greatest of King Louis’ Musketeers, Athos, Porthos, and Aramis, must prevent the evil Cardinal Richelieu from securing an alliance with the English Duke of Buckingham, assassinating King Louis XIV, and taking over France. They’re joined by an eager newcomer and would-be Musketeer, D’Artagnan, who desperately seeks to live up to his slain father’s example of heroism. To complicate matters, the Musketeers have been disbanded, and our heroes are on the run from the Cardinal’s men and allies, including the expelled Musketeer, Rochefort, and the deadly femme fatale, Lady Sabine DeWinter. It’s an exciting and danger-fraught race against time to save the King and France. That’s the basic story. It’s filled with twists and turns, chases and duels, captures and escapes. D’Artagnan, in particular, falls into trouble with frightening regularity, but always at the right time to overhear a crucial detail or foil a vital part of the evil plan. Meanwhile, the others struggle with their various quirks and quips, though it must be said, the movie goes heavy on quips and action, relatively light on the more profound elements.

The characters shine; the actors have just the right chemistry, playing off one another with near-perfect comic timing. Charlie Sheen stars as the religious (yet attractive to women) Aramis, while Keifer Sutherland takes a turn as the intense, driven “leader” of the group, Athos, whose shadowed past may rise up to bite him once again. It’s a sad fact that, when I try to recall this movie, the two of them manage to blend into one uber-Musketeer, overshadowed as they are by the rest of their illustrious companions. Neither Sheen nor Sutherland disappoint, they merely have trouble standing out from one another… a rare fault in an otherwise wonderful movie. Oliver Platt, as the cheerfully over-the-top Porthos, steals the show every chance he gets. This Porthos is confident, creative, and armed with a saucy or pithy quip for every occasion. Spouting sayings like, ‘This scarf was a gift to me from the Tzarina of Tokyo” and “This Bible belonged to the Empress of America”, sporting nifty-keen weapons such as a sword-breaker and a keenly-thrown bolo, he swaggers through the movie shamelessly. I’ve always enjoyed Oliver Platt’s work; his range of facial expression and ability to play comic characters without descending into buffoonery has always been a highlight of any movie he’s in. In this film, he rules. He’s perhaps the most anachronistic, his phrasings often suspiciously modern but, in the atmosphere he brings with him, it’s acceptable. Chris O’ Donnell turns in a brilliant performance as the wide-eyed, Musketeer-idolizing, overconfident neophyte, capable of arranging three duels in one day and believing he’ll survive them all. A sucker for a pretty face, the stranger in the crowd, he’s set up as the viewpoint for the story, so that we follow him through the action. Through this oft-used but still serviceable trope, we are introduced to the world of the Musketeers from the viewpoint of someone lacking in that experience.

The villains are every bit as delightful as the heroes. Tim Curry is larger-than-life, a moustache-twirling, sneering evil genius, in the guise of Cardinal Richelieu. He’s capable of ordering a man’s death or plotting an assassination, able to sway people with his used car salesman oily charm, perfectly at home sweeping through rooms in his blood-red robes. He’s ambitious and dangerous, without mercy or hope of redemption, broadly painted as the bad guy, and he excels. His trusty accomplice, the one-eyed ex-Musketeer, Rochefort (played by Michael Wincott), is dark and sinister, speaking his pronouncements of doom in a gravelly voice. Dressed in black, he makes the perfect right-hand-villain, his personal history with the Musketeers giving their exchanges that snap and bite you only find among ex-coworkers or ex-lovers. And he’s set up as D’Artagnan’s arch-enemy, the first true test of his heroic status, in a clever manner. Rebecca De Mornay is a seductive ice queen as Lady Sabine DeWinter, the Cardinal’s distrusting messenger and occasional personal foil. She’s always in control, cool and collected, pale and beautiful, and the most dangerous of the lot.

This is a movie with an ear for dialogue and a way with snappy repartee. The Musketeers banter to one another while barreling along on a stolen coach, the Cardinal’s men in hot pursuit. D’Artagnan trades insults with Porthos and friends. Lady DeWinter and the Cardinal threaten each other as each tests the other’s resolve. Perhaps it’s a bit too light and witty at times, but it’s fun all the same.

The action sequences are exciting, swashbuckling sword-fights that take advantage of multiple levels, runaway horses, stairs, chandeliers, boats, and various opponents. This is no wire-fighting extravaganza as the recent Musketeer was but, in its own way, these sequences are just as thrilling.

Throw in an elegant soundtrack featuring the Bryan Adams/Rod Stewart/Sting collaboration “All For Love”, and sweeping operatic symphonies in the background, exquisite costuming and gorgeous locations for the scenery and, all in all, what you have is a genuinely enjoyable, unashamedly fun movie that takes the very best of The Three Musketeers and translates them for a new audience. Disney may not always respect the source material (as witnessed by the animated Hunchback of Notre Dame), but when they do something right, they really outdo themselves.

The Three Musketeers was directed by Stephen Herek, and adapted from the original novel by Alexandre Dumas for screenplay by David Loughery. It starred Chris O’Donnell (D’Artagnan), Keifer Sutherland (Athos), Charlie Sheen (Aramis), Oliver Platt (Porthos), Tim Curry (Cardinal Richelieu), Rebecca De Mornay (Lady DeWinter), Michael Wincott (Rochefort), Hugh O’Conor (King Louis XIV), Julie Delpy (Constance) and Gabrielle Anwar (Queen Anne). It runs 105 minutes and is available on tape or DVD.

One of the great tropes of the fantasy genre is the high epic fantasy, the story of Good vs. Evil in an all-out war to determine the fate of the world. Heroic warriors and paladins, mighty wizards, cunning rogues, elegant elven archers, and magical weapons. Evil overlords, trolls and orcs and goblins, the legions of darkness. In the end, Good always wins, right? Now, see the story told from a decidedly different point of view, as the bad guys get their chance to shine.

One of the great tropes of the fantasy genre is the high epic fantasy, the story of Good vs. Evil in an all-out war to determine the fate of the world. Heroic warriors and paladins, mighty wizards, cunning rogues, elegant elven archers, and magical weapons. Evil overlords, trolls and orcs and goblins, the legions of darkness. In the end, Good always wins, right? Now, see the story told from a decidedly different point of view, as the bad guys get their chance to shine.