As this title suggests, the common denominator is that each of the fifteen stories within focuses upon a female, be they soldier, warrior, or innocent caught up in times of war. Thus, we’ve got a mixture of military science fiction, fantasy, action, and girl-power.

As this title suggests, the common denominator is that each of the fifteen stories within focuses upon a female, be they soldier, warrior, or innocent caught up in times of war. Thus, we’ve got a mixture of military science fiction, fantasy, action, and girl-power.

Some of the authors take the opportunity to visit previously-established characters. Sharon Lee and Steve Miller give us a short story exploring the pre-military life of Miri Richardson, who plays a major role in their Liaden Universe books, in “Fighting Chance,” and they show us how the headstrong young woman joined up in the first place. Tanya Huff drops in on Staff Sergeant Torin Kerr, heroine of her Valor books, in “Not That Kind of War.” It’s a short but sharp piece that exposes the characters to the pointless brutality of a quiet war. Bruce Holland Rogers’ “The Art of War” puts a human defense group up against an implacable, indecipherable enemy which lays waste to entire planets. It’s up to one woman to figure out the strange secret of the alien attackers before they destroy yet another world for no reason. In “Elites,” by Kristine Kathryn Rusch, one old veteran has found a kind of peace in running a halfway house for other vets, those women who just can’t escape the trauma of their military service. However, is our heroine as well-adjusted as she thinks she is, or has she yet to find her own healing?

While there are some very good stories in here, including ones by Jane Lindskold, Rosemary Edghill, Julie Czernada, and Stephen Leigh, I must confess that many of them didn’t really catch my fancy, making this a case where I skipped over more stories than I like. However, it’s still a strong selection, both of authors and of themes addressed, and I definitely found some stories that made me think.

This anthology explores the concept of gateways, with each of the 29 original stories collected within detailing a different portal, of one kind or another. Whether they link distant galaxies, the past and future, or even life and death, they all manage to bring two very different realms together.

This anthology explores the concept of gateways, with each of the 29 original stories collected within detailing a different portal, of one kind or another. Whether they link distant galaxies, the past and future, or even life and death, they all manage to bring two very different realms together.

One of the oddest stories in the book has to be Robert Sheckley’s metafictional story, “The Two Sheckleys,” about an author named, what else, Robert Sheckley, who gets invited to write a story about, what else, gateways. Before it’s over, there’ll be more than one Robert Sheckley, and they’ll both travel into distant realms in search of a story. Russell Davis’ story, “Midnight at the Half-Life Café” finds a long-hospitalized man journeying into a strange limbo realm, where he’ll make the most fateful decision of his life in a mysterious nocturnal café. Rebecca Moesta’s charming “Postcards” links two very different, yet similar, girls across universes, offering one of them a possible way out of a bad situation. Daniel Hoyt’s “Shift Out Of Control” takes a look at parallel dimensions and alternate timelines, and addresses just how confusing it can all be to those unprepared for the infinite possibilities. In Janet Deaver-Pack’s “The Trigger,” a young woman, missing for years, returns with a bizarre story about visiting a whole new world. How she got there, and how she got home, is the mystery, but after meeting her parents, is it any wonder she wants to go back?

Rebecca Lickiss’ “Spring Break” is a howlingly funny, off-color tale of pirates, fairies, and one very lost teenager. In “Double Trouble,” John Zakour revisits the future of Zachary Johnson, the last P.I. on Earth, as he investigates a mystery involving time travel. “By the Rules,” by Phaedra Wilson, follows a group of gamers who get a little too involved in their current game, literally sucked into the setting. In Jim Fiscus’ “Carded,” a man set on some corporate revenge finds both enemies and allies in another dimension, due to a case of mistaken identity.

These are just some of the entertaining, and quality, stories to be found in this collection. Clearly, the authors all had a lot of fun in exploring their theme, and they certainly didn’t hold back in stretching the idea to its limits. This was definitely a good collection, with something bound to appeal to just about any fan.

Inspired by, though not based upon, the Low Port setting from Sharon Lee and Steve Miller’s popular Liadan series, Low Port is a collection of stories aimed at giving characters who normally remain in the background a turn to shine. We all know these characters: the bums, grifters, con men, barmaids, merchants, drifters, the people who aren’t necessarily heroes or villains, the ones who get by while the more dramatic people do their thing. And these aren’t the humble farmers or assistant pig-keepers or orphans destined for great things, either. They’re the white noise in the background, the crowd scenes, the spear-carriers.

Inspired by, though not based upon, the Low Port setting from Sharon Lee and Steve Miller’s popular Liadan series, Low Port is a collection of stories aimed at giving characters who normally remain in the background a turn to shine. We all know these characters: the bums, grifters, con men, barmaids, merchants, drifters, the people who aren’t necessarily heroes or villains, the ones who get by while the more dramatic people do their thing. And these aren’t the humble farmers or assistant pig-keepers or orphans destined for great things, either. They’re the white noise in the background, the crowd scenes, the spear-carriers.

Hence, in Low Port, you’ll find a wide variety of characters. The main character of John Teehan’s “Digger Don’t Take No Requests” is a musician and con man who’s currently holding the record for longest transient inhabitant of the Moon, having spent nearly five years trading on unexpired visa chits to stay where he belongs. But time’s got to run out for everyone, and sooner or later, Joe’s going to be sent back to Earth, unless he can wrangle an unusual solution. After all, there’ll always be a need for dishwashers and janitors in space.

The winner of Most Unusual Title is Edward McKeown’s “Lair of the Lesbian Love Goddess,” a down-and-dirty cop story of a decidedly unusual beat. Rest assured, it’s not what you think, which may just be a good thing. Nathan Archer’s “Contraband” introduces Jeffers, a customs officer willing to bend the rules to line his own pocket. However, when he stumbles across a unique cargo, he learns that he’s not entirely devoid of scruples. But what’s a guy to do when everything looks okay on paper? Get creative, that’s what.

In “Spinacre’s War,” by Lee Martindale, a disgraced military commander is placed in charge of an obscure, unremarkable territory on the edge of nowhere. When he decides to abuse his power and “lose” the people he’s been assigned to care for, he sets a chain of events in motion that will ultimately force a reckoning between town and military base. But really, what chance does a ragtag band of whores and cripples stand against finely-trained military men? In “Bottom of the Food Chain,” by Jody Lynn Nye, we’re introduced to Hap, one of the many forgotten, disenfranchised residents of the Belowstairs section of Delta Station. Just another have-not, in a community that couldn’t even tell you what they don’t have, Hap has some big dreams. Then a stroke of luck delivers a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity into his lap. Granted an effective blank check, with the sky the limit, what will he reach for?

In “The Times She Went Away” by Paul E. Martens, the legendary Annie Jones changes a man’s life everytime she walks into it… and out again. A pirate, smuggler, hero, villain, thief, scoundrel, mercenary, and much more, Annie dominates the scene wherever she goes. But for Peter, a mild-mannered poet, she’s an inspiration, and the touchstone by which he’s measured his life. For every hero that strides the stars, there’s a poet or lover or dreamer in every port, and here, we see what effect the hero has on those whose lives they intrude upon.

These are just a few of the twenty stories which make up Low Port. Spanning science fiction and fantasy, including authors such as Sharon Lee, Lawrence Schoen, Ru Emerson, and eluki bes shahar, this is a highly imaginative, rather eclectic collection, with a little something for everyone. Low Port is great fun, and it sheds light on settings and characters rarely given the attention. Lee and Miller clearly have a knack for picking interesting and entertaining stories.

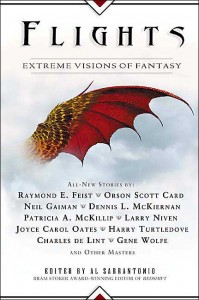

Following up on his previous anthology, Redshift, which was a collection of science fiction stories that sought to redefine the boundaries of expectations, Al Sarrantonio has now come out with the companion volume, which looks towards raising the bar for fantasy in terms of quality and imagination. Flights is a massive volume as far as anthologies go: 560 pages and over 200,000 words, broken down 29 stories of varying lengths, ranging from short-short to novella.

Following up on his previous anthology, Redshift, which was a collection of science fiction stories that sought to redefine the boundaries of expectations, Al Sarrantonio has now come out with the companion volume, which looks towards raising the bar for fantasy in terms of quality and imagination. Flights is a massive volume as far as anthologies go: 560 pages and over 200,000 words, broken down 29 stories of varying lengths, ranging from short-short to novella.

The authors represented within are some of the very best in the field, including Charles de Lint, Larry Niven, Nina Kiriki Hoffman, Robert Silverberg, Neil Gaiman, Harry Turtledove, Orson Scott Card, Jeffrey Ford and Gene Wolfe. With everything from high fantasy to urban fantasy to fantasy that defies casual categorization, this is easily one of the more impressive collections to hit the shelves this year thus far. There’s no way I can discuss every single story, not without running way over my limit, so let me present a few, taken from the book like snapshots.

Joe Lansdale’s “Bill, the Little Steam Shovel,” is presented as one might a children’s book. Certainly on the surface, the adventures of a steam shovel who just wants to do the very best he can would seem like a children’s story, but in this word, steam shovels aren’t all innocent and pure and sparkling. They have needs and desires and use foul language when no one’s looking, like the rest of us. While I’d love to see this one properly illustrated, I’d be afraid to leave it lying around for the kids. For adults, it’s great fun, however.

L.E. Modesitt’s “Fallen Angel” is an unusual, somewhat sad look at a different side to the relationship between Heaven and Hell, and between the angels who stayed, and the one who fell the furthest. It’s a fascinating premise, but may require more than one reading to fully get all the subtleties.

Dennis L McKiernan retells an old and familiar fairy tale in “A Tower With No Doors.” There’s a prince, a witch, and a lovely maiden trapped in a high tower. But not everything is as it seems.

In “Riding Shotgun” by Charles de Lint, a man with a troubled past gets a chance to change it, only to discover that the price he pays is more than just his life. Has his atonement, however, unleashed something even worse? Part ghost story, part urban legend, part time travel, it’s a complex cycle of events which lead into unexpected territory, but with hope always at the end of the tunnel. Though de Lint’s tackled some of these themes before, he still manages to make them feel fresh and new, and his solution is inventive without wrapping things up too neatly.

Kit Reed delivers a story about the day after the end of the world, in “Perpetua.” A family of miniaturized survivors travel in a specially outfitted alligator, avoiding the disasters which have made the outside world all but uninhabitable. But for one girl, survival is nothing without the man she loves, and the bond she forges with the alligator could save or doom them all. Plain and simple, I love the concept, and the imagery the story conjures up.

Peter Schneider gives us “Tots,” which does for four-year-olds what cockfighting did for chickens. Yes, two toddlers enter, one toddler leaves. I don’t know whether to be fascinated, appalled, or both. But then again, that’s part of the magic of the genre: anything is possible with the right twist of imagination.

Neil Gaiman’s “The Problem With Susan” can be looked at as an unofficial epilogue to the Narnia books. After all, whatever did happen to Susan, the only one of the four children not to show up for The Last Battle? What if she carried on and grew up? But that’s not the whole story. This is a dreamlike story, casting the characters in a strange new light, placing subversive, thoughtful suggestions regarding the Lion and the Witch (but no wardrobe), as well as the nature of Mary Poppins and of childrens’ books. It’s a typically Gaimanesque piece, taking the familiar and twisting it around so that we’re forced to reconsider what we’ve always known, making us reevaluate and reappreciate it.

The above stories are just the tip of the iceberg. What can I say, except that if you love fantasy in any of its forms, and you enjoy short fiction, Flights may very well be the don’t-miss collection of the year, sure to produce some award nominees and award winners, and maybe a few new classics. Miss this, and you’ll be losing out on something rich and strange.

Now in its second decade of existence, the Writers of the Future competition continues to turn out new authors in an inexorable, almost mechanical process. Each year, fourteen winners are chosen from the best stories submitted in each of four separate quarters, and selected to appear in the yearly showcase anthology. Thousands may enter, but little over a dozen writers, and just as many illustrators, are chosen for fame and fortune. Admittedly, there are those who have their doubts about WOTF, or its spiritual founder, the late great L. Ron Hubbard, but the truth is evident: the WOTF program has started any number of writers on the path to professional publication, including James Alan Gardner, Sean Williams, Nancy Farmer, and Robert Reed, to name just a few.

Now in its second decade of existence, the Writers of the Future competition continues to turn out new authors in an inexorable, almost mechanical process. Each year, fourteen winners are chosen from the best stories submitted in each of four separate quarters, and selected to appear in the yearly showcase anthology. Thousands may enter, but little over a dozen writers, and just as many illustrators, are chosen for fame and fortune. Admittedly, there are those who have their doubts about WOTF, or its spiritual founder, the late great L. Ron Hubbard, but the truth is evident: the WOTF program has started any number of writers on the path to professional publication, including James Alan Gardner, Sean Williams, Nancy Farmer, and Robert Reed, to name just a few.

Volume 19 is no different. The (mostly) unknown authors appearing in this collection may very well be the same authors gracing the bookshelves a few years down the road. As always, the stories show both a wide range of potential, and a wide range of styles. In all honesty, I’ve never enjoyed more than half of the stories in any given WOTF volume, but that merely proves that there’s a little something for everyone. Perhaps you’ll enjoy Joel Best’s unusual tale of creative mathematics, “Numbers.” Maybe Matthew Candelaria’s story of uneasy alien diplomacy, “Trust Is A Child” is more your speed.. There’s always Carl Frederick’s oddly touching “A Boy and His Bicycle,” which takes friendship to a new level. These, and eleven others, await you.

It’s always hard to pick out the best stories from anthologies like these. Without a common theme, choosing from fantasy and science fiction, they tend to be a bit scattershot. However, the quality tends to be high, as the judges of the contest are all themselves published authors with distinguished track records. Writers of the Future is a grab-bag anthology, but an enjoyable one, almost always worth checking out.

There are days when I love theme anthologies. You have a vague idea of what you’re getting, and they approach the same ideas with such a wide variety of styles that there’s usually something for everything. Denise Little has put together some really nice collections in the past few years, and it’s gotten to the point where, if I see her name as editor, I know I’m in for a worthwhile read. The Magic Shop is another such anthology. Once I started, I pretty much read it straight through. As can be inferred from the title, the common element in all of the stories revolves around magic shops that deal in, sell, or are associated with “real” magic, in addition to, or instead of, stage and parlor tricks. This is nothing new; stories about mysterious shops selling magical items have been a staple of the genre for decades. However, it’s still a theme full of potential, as these fifteen stories indicate.

There are days when I love theme anthologies. You have a vague idea of what you’re getting, and they approach the same ideas with such a wide variety of styles that there’s usually something for everything. Denise Little has put together some really nice collections in the past few years, and it’s gotten to the point where, if I see her name as editor, I know I’m in for a worthwhile read. The Magic Shop is another such anthology. Once I started, I pretty much read it straight through. As can be inferred from the title, the common element in all of the stories revolves around magic shops that deal in, sell, or are associated with “real” magic, in addition to, or instead of, stage and parlor tricks. This is nothing new; stories about mysterious shops selling magical items have been a staple of the genre for decades. However, it’s still a theme full of potential, as these fifteen stories indicate.

In “Every Little Thing She Does,” Susan Sizemore introduces us to a reluctant hero-turned-bookseller who gets called in to deal with a legendarily dangerous house, and finds more than he bargained for in the feminine charms of his client. P.N. Elrod’s “Tarnished Linings” looks at the oddballs attracted by a magic store, including a part-time computer geek, two college-age Wiccans, a conjured demon, and a teen on the fast track to self-destruction. In “For Whom The Bell Tolled,” by Jody Lynn Nye, the owner of a magical curio shop finds a real surprise in a genuine magical artifact that spells the end to his boredom … and almost an end to his business.

Laura Resnick’s “The Magic Keyboard” offers one starving writer the chance to change her luck, as well as her writing style. But can the objects that once belonged to other writers help her to unlock her true potential? In Bradley H. Sinor’s “Grails,”a favor to a stranger leads one man to a store where he’ll find just what he needs, with no promises as to whether he’ll understand that need. Josepha Sherman’s story, “Mightier Than The Sword?” also features a writer in a jam, and the only thing that can save her is … a cheap ballpoint pen?

Meanwhile, in Kristine Kathryn Rusch’s “The Assassin’s Dagger,” a corporate troubleshooter for the world’s largest chain of magic stores has to deal with the nasty unfinished business of a new corporate acquisition. Gary Braunbeck turns in a rather moody little piece about true magic and sacrifice in “The Hand Which Graces,”and Rosemary Edghill returns to her popular Bast character in “A Winter’s Tale.” Stories by ElizaBeth Gilligan, Michelle West, Bill McCay, Mel Odom, India Edghill and Von Jocks finish off the book. I really enjoyed The Magic Shop, and can easily recommend just about every story in it.

I’ve had this book since it first came out, reading it in small doses both to savor the contents, and to avoid from overloading my brain with too many ghost stories all at once. For that’s the theme here. Ellen Datlow asked a number of authors to come up with new ghost stories for the modern era, stories to disturb and discomfort and cause restless nights and bad dreams. I’m happy to say that she succeeded, with The Dark. Frankly, while they were appropriately spooky back in October, the stories are even more effective in the dead of winter, with the long nights and the constant feeling of being cold whenever you go out. (Admittedly, this is a regional thing; those who can wear Bermuda shorts in winter, not a word out of you.)

I’ve had this book since it first came out, reading it in small doses both to savor the contents, and to avoid from overloading my brain with too many ghost stories all at once. For that’s the theme here. Ellen Datlow asked a number of authors to come up with new ghost stories for the modern era, stories to disturb and discomfort and cause restless nights and bad dreams. I’m happy to say that she succeeded, with The Dark. Frankly, while they were appropriately spooky back in October, the stories are even more effective in the dead of winter, with the long nights and the constant feeling of being cold whenever you go out. (Admittedly, this is a regional thing; those who can wear Bermuda shorts in winter, not a word out of you.)

As with any anthology, certain stories leap out. For me, those include Tanith Lee’s “The Ghost of the Clock,” which imbues a simple household item with a deadly history and an eerie nature, and Joyce Carol Oates’ “Subway,” in which a young woman races inexorably towards her ultimate destination, and her final fate. Both of those possess the power to make me shiver a little with anticipatory dread at turning out the lights, in their own way.

They’re not alone, of course. Jack Cady’s “Seven Sisters” reinvents the subgenre of the haunted house to great effect, offering up enough fascinating characters and concepts to warrant an entire book on the subject. When fine architecture and immortal obsessions collide, a town feels the consequences in something straight out of Stephen King’s finer moments. Sharyn McCrumb’s “The Gallows Necklace” is a chilling tale of youthful indiscretion, repeated mistakes, and casual cruelty, with the past refusing to stay buried. Kathe Koja explores a different sort of obsession and another haunted house in “Velocity.” Jeffrey Ford, Gahan Wilson, Kelly Link and others also add to the spook factor with their own stories. All in all, The Dark is exactly what it sets out to be: an excellent collection of stories that’ll creep you out late at night, and now’s as good as time as any to check it out.

Partially in honor of the International Space Station to be completed in 2006, and in memory of those orbiting habitats which have come and gone such as Skylab and Mir, Space Stations is an anthology of original stories which all revolve around the theme of space stations, both manmade and otherwise. Fourteen authors have taken on the subject, and the results are both varied and fascinating.

Partially in honor of the International Space Station to be completed in 2006, and in memory of those orbiting habitats which have come and gone such as Skylab and Mir, Space Stations is an anthology of original stories which all revolve around the theme of space stations, both manmade and otherwise. Fourteen authors have taken on the subject, and the results are both varied and fascinating.

While all of the stories are good, some stand out more than others. Julie Czernada’s “The Franchise” marks her return to the worlds of In The Company of Others, following up on the events of that novel. With the deadly Quill Effect a thing of the past, humanity is finally free to move beyond its boundaries. For generations born and raised on overcrowded space stations, this is both a new beginning, and a new challenge. But before humanity can step onto new worlds, they have to reclaim and rehabilitate long-abandoned space stations, and on one such station, a mystery remains to be solved, its answer lying somewhere in the past.

Robert Sawyer’s “Mikeys” takes a different look at space exploration, as the first manned trip to Mars reveals some unusual facts about one of the red planet’s moons. The real story, however, focuses upon the “Mikey” of the trip, so named for Mike Collins, the Apollo 11 astronaut who went to the Moon, but never set foot on the surface. Will the underdogs have their day?

In “Redundancy,” Alan Dean Foster tells the story of a truly unusual space station, one that manages to overcome its normal programming to accomplish the heroically unthinkable. This actually creates a resonance with Russell Davis’ “Countdown,” which details the last moments of one station and its last commanding officer, in a poignant tale of sacrifice and defiance. In”Falling Star,” Brenda DuBois looks at a world where technology has regressed, from the viewpoint of someone who once traveled among the stars. Here, the focus is clearly on what the lack of a space station might mean.

Those are only a handful of the stories to be found in Space Stations, as well as contributions by Timothy Zahn, Jean Rabe, Jack Williamson, Gregory Benford, Michael Stackpole and more. As collections go, it’s a fairly strong one, one that’s even topical given the slight progress we’ve been making in exploring Mars lately and the possible future of our push into space. I was quite pleased with the stories within.

When I received this, I was hoping it would be along the lines of the excellent anthology, Superheroes, edited by John Varley and Alicia Mainhardt (Ace, 1995). Based on the roleplaying game Silver Age Sentinels, Path of the Just contains fifteen stories of superheroes and villains, all set in a shared universe and primarily based in the fictional Empire City. Now, superhero fiction is hard enough to do normally; four-color exploits don’t necessarily lend themselves well to simple prose. Path of the Just suffers somewhat from its origins with a roleplaying game; as with any such spinoff, there’s the image that one needs to be familiar with the game in question. The common threads linking the stories constantly hint at a much larger background and theme, without actually filling in some of the necessary blanks regarding history, origins, or even the nature of some teams. Furthermore, I found it somewhat confusing that some of the “signature characters” so prominently mentioned on the cover don’t even appear in this collection. I can only surmise that these are important to the game, if not the fiction.

When I received this, I was hoping it would be along the lines of the excellent anthology, Superheroes, edited by John Varley and Alicia Mainhardt (Ace, 1995). Based on the roleplaying game Silver Age Sentinels, Path of the Just contains fifteen stories of superheroes and villains, all set in a shared universe and primarily based in the fictional Empire City. Now, superhero fiction is hard enough to do normally; four-color exploits don’t necessarily lend themselves well to simple prose. Path of the Just suffers somewhat from its origins with a roleplaying game; as with any such spinoff, there’s the image that one needs to be familiar with the game in question. The common threads linking the stories constantly hint at a much larger background and theme, without actually filling in some of the necessary blanks regarding history, origins, or even the nature of some teams. Furthermore, I found it somewhat confusing that some of the “signature characters” so prominently mentioned on the cover don’t even appear in this collection. I can only surmise that these are important to the game, if not the fiction.

Those quibbles aside, every story has its strengths, while some stand head and shoulders above the rest. My personal favorites had to be Steven Grant’s “Citizens,” in which a demoralized supervillain gets one last shot at a legendary vigilante hero, and “Ion Shells” by Steven Harper, which looks at an unusual relationship blossoming between a superhuman thief, and the hero who keeps running afoul of him. John Ostrander’s “Hardball” tells a story of courage and determination heedless of sacrifice, and J. Allen Thomas’ “Decisions” focuses not upon the superhumans, but on the humans affected by their actions. “Covalent Bonds,” by Erika Schippers, studies an unusual woman, and her bar, which acts as neutral territory for supervillains. Robin Laws gives us “The Final Equation,” in which a hero is granted one last talk with a notorious killer and learns some very dark history. Both moralistic and metafictional, it’s an odd piece that doesn’t quite sit right in relation to some of the other stories. “Apocalypse” by Daniel Ksenych is both one of the most promising and most frustrating offerings, focusing on a semi-reformed villainess and the hero team that’s given her shelter. The story hints at so much more to the setting, and yet explains so little.

I’m sure fans of the game will love this book. Also, it’ll appeal to comic book fans, and those left hanging when the steady stream of Marvel Comics-based fiction all but dried up completely. I am looking forward to the next collection from this publisher, if just to see what other stories they have to tell.

In this anthology, noted author Gregory Benford collects a baker’s dozen of stories that all explore the concept of limited spaces, or microcosms. As usual, the stories range the spectrum from good to excellent as the authors take the concept and run with it. Jack McDevitt gives us a really strong story in “Act of God,” where a group of scientists have figured out how to create a miniature universe, one they can actually watch and affect. But what consequences will playing God have for their creation, and for them? What unforseen factor could ruin their entire experiment?

In this anthology, noted author Gregory Benford collects a baker’s dozen of stories that all explore the concept of limited spaces, or microcosms. As usual, the stories range the spectrum from good to excellent as the authors take the concept and run with it. Jack McDevitt gives us a really strong story in “Act of God,” where a group of scientists have figured out how to create a miniature universe, one they can actually watch and affect. But what consequences will playing God have for their creation, and for them? What unforseen factor could ruin their entire experiment?

Robert Sawyer’s “Kata Bindu” is just as strong, the story of an African tribe relocated to the Moon to live in isolation, the only human beings not to participate in the great evolution of collection consciousness. Could these hold-backs provide the key to the true evolution of the species? Meanwhile, in “Ouroborous,” Geoffrey Landis looks at life as nothing more than a complex simulation, then exploring the idea of how far such a simulation can go. Could it, perhaps, create a simulation of its own, and so forth, multiple realities dwindling into an artificial infinity? Mike Resnick and Dean Wesley Smith take the concept of a microcosm to an interesting extreme in “A Moment of Your Time,” in which humanity solves the problem of overcrowding by sponsoring relocation efforts, sending groups of people into the past, where they spend decades trapped in a single unchanging moment in time. But what significance does 12:36, August 10, 2002 have for one group of temporal squatters?

This is just a sampling of what awaits in Microcosms, with stories by Stephen Baxter, Pamela Sargent, Paul Levinson, Robert Sheckley and more rounding out the collection. It’s a first-rate effort, though some stories didn’t grab me as much as others.