The Faeries, by Suza Scalora (Joanna Cotler Books/Harpercollins, 1999)

The Faeries, by Suza Scalora (Joanna Cotler Books/Harpercollins, 1999)

The Faeryland Companion, by Beatrice Phillpotts (Barnes and Noble, 1999)

The Leprechaun Companion, by Niall Macnamara with Wayne Anderson (Barnes and Noble, 1999)

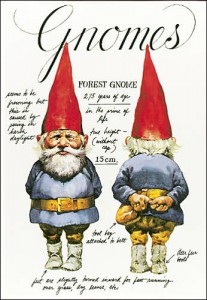

Gnomes, by Wil Huygen and Rien Poortvliet (Peacock Press/Bantam Books, 1979)

The Kingdom of the Dwarves, by Robb Walsh and David Wenzel (Centaur Books, 1980)

The Hobbit Companion, by David Day with Lidia Postman (Turner Publishing, 1997)

The Great Encyclopedia of Faeries, by Pierre Dubois with Claudine and Roland Sabatier (Simon and Schuster, 1999)

The Fairies’ Ring, by Jane Yolen with Stephen Mackey (Dutton Childrens’ Books, 1999)

“I have gone out and seen the lands of Faery,

And have found sorrow and peace and beauty there,

And have not known one from the other, but found each

Lovely and gracious alike, delicate and fair.”

-“Dreams within Dreams” by Fiona Macleod

Open your eyes to the world around you. There are things, there, living and hiding often in plain sight. We know them by many names: The Fair Folk, fairies, gnomes, goblins, dwarves, brownies, elves, tommyknockers… the list is endless, with as many names for the creatures of fancy and myth as there are people to dream of them and tell their stories. Are they real, or just figments of our imaginations, created to pass the time and explain away mysteries in a much more superstitious era? That, I must say, is up to you to decide. But gathered for your entertainment and approval are a handful of coffee table books, art books full of paintings, photography, stories, poems, and even scholarly analysis of the hidden world.

First up is an absolutely gorgeous little book, The Fairies, by Suza Scalora. Detailed as “Photographic Evidence of the Existence of Another World,” it’s certainly easy to conclude from the photos within that fairies really do exist. Presented with a playful sort of seriousness, it lays out each of the twenty-six entries, or “plates” in the same fashion. On the left page is the entry for the fairy in question, detailing their common name, other known names, the date and location of the particular sighting, and the season in which said fairy is most likely to be seen. Following that is a short history of the creature, the particular lure used to bring it out into the open, and finally notes on the specific encounter. On the right is a full-color glossy photograph of the fairy in its natural environment

Now, these aren’t your traditional fairies, the ones well-recorded throughout history. These sport names like Ophelia, the Pearl-White Fairy, or Willow, the Silver Leaf Fairy. They lurk in the woods of Georgia, a glacier in the Icelandic highlands, the lush valleys of Peru, Hawaii, or even the Neolithic goddess temples of Malta. They embody fire and ice, air and sky, birds and trees. Each one is unique and fantastical, playful and whimsical and capricious. They can be lured by pencils, bright balloons, fireflies, salt, or even just simple trespass into their domains. And they are elusive.

Of all of the books I’ve seen in putting this review together, The Fairies may be the most beautiful from an artistic standpoint. The conscious mind may be secure knowing that the photos are all cleverly-doctored, involving humans in costume and makeup, but the child-like, magic-seeking part of me wanted to believe, if even for just a moment. More than anything, this book captures the sheer alien nature of the fairies, the way they can be seen out of the corner of your eye, when the light and mood is just so. I was initially attracted by the artistic value of this book, and I’m quite pleased by it.

While we’re on the subject of fairies, we’ll move along to Beatrice Phillpotts’ The Faeryland Companion. This one seeks to be a more comprehensive look at fairies in history, art, and literature, starting with a look at fairies in their natural environments and ending with their role in art.

This is quite the informative book, really. The very first entry lists over half a dozen different theories on the origins of the Fair Folk, from unforgiven souls to diminished pagan dieties. It looks at the places they’re most commonly associated with: underground kingdoms, enchanted forests, even somewhere out in the ocean. It examines them as tiny creatures and hulking giants, as creatures of enchantment and beings of mystery. It details all of the customs traditionally associated with them, such as fairy rades or household assistance, or music and dance. There’s a section that tells about fairies and their interactions with humans, both benevolent and malevolent, from fairy godmothers to changeling children and even the time differential between their world and ours. Finally, the section on art touches upon the Victorian fascination with fairies, the incident involving supposed photographic proof of fairies (which fooled just about everyone), and then ends with a look at that modern master himself, Brian Froud.

The Faeryland Companion is a well-constructed book, worth checking out for its wealth of lore and art, collected from many different sources. While it doesn’t have the in-depth examination that some works might, it balances out information and accessability, and still comes out looking quite pretty. It looks at them with a historical and popular sort of view, drawing in bits of poetry, Shakespearian quotes, Froud artwork, and more. Definately a nice effort that doesn’t disappoint.

In that same vein, also released as a Barnes and Noble exclusive is The Leprechaun Companion by Niall Macnamara, illustrated by Wayne Anderson. It does for leprechauns what Brian Froud’s Faeries did for, well, fairies. However, this has a much more Celticentric angle to it, looking at the indiginous fairyland creatures which inhabit that part of the world. It seeks to tell the truth of leprechauns, that they’re not always as cheerful as one might suppose; that indeed they can be quite cantanerous and capricious. It has details on how to look for leprechauns, and also how to avoid them. Though they go by many different names, from clurichauns to luchrymen, the book lumps them as leprechauns for ease of clarity. We go into the details of their society: food, work, courtship, dwellings, drink, even fashion. We learn how to bottle them, and why it’s not always smart. We learn about their holidays, games, music, and of course, magic.

Once we have the basics out of the way, the book happily goes into the details of the various leprechaun clans, which roughly divide themselves between the provinces of Ireland: Leinster, Munster, Ulster, and Connaught, ultimately overseen by the Sidhe, the kinglike race of the fairies descended from the primeval Tuatha de Danaan. Each clan has its own defining characteristics and natures, as well as associated legends and tales.

In the last chapter, we’re introduced to a host of leprechaun cousins, a motley assortment of Celtic creatures from myth and legend. Merpeople, fir dearg, phouka (like our old friend from War For The Oaks!), brownies, redcaps, bwca, piskies, spriggans, and more. Each one has a short description of nature and history, as well as an associated tale to accompany it.

This is a very nice book. The artwork is appropriately stylized and whimsical, taking a more humorous, old-fashioned view of the creatures in question, slightly cartoonish without losing their dignity. It’s nowhere near as evocative as Froud’s, but it certainly does the job quite well. If you like Celtic myth and fairy tales, this book might be worth checking out.

Since we’ve gotten onto the topic of scholarly volumes regarding creatures of myth, it’s only natural to skip next to Gnomes, a 1979 release from Wil Huygen and Rien Poortvliet which really did set the stage for many of these other books. It has a distinctly European feel and bias to it, looking at the world of the woodland gnomes of Europe, Russia, and Siberia, but also branching out to discuss other related beings.

Where to begin? Quite simply, this book lays it all out in its multitudinous entries, from history and legends to their very physiology and medicine. To detail it would be an exercise in futility, as it’s crammed full of sketches, drawings, paintings, essays, tales, speculation and examination. Open to a random page, and read about their breakfast. Another page has a drawing of a gnome skeleton. There’s a look at their digestive system, for example, and maps showing population density across Europe and North America. The list goes on.

I adore this book. Very few can come close to it in terms of constructing a full-fledged, believable society for mythical creatures, and present it in such a charming, accessible, artistic package. The associated art ranges from serious to whimsical, and never loses track of the fey qualities of the gnomes within. (But what’s up with those pointed red hats? I think there’s a section devoted to that question…) If you like Froud’s Faeries, this book is essential for your collection.

Lest no underground-dwelling creature of myth be left out, next on the list is Kingdom of the Dwarves, by Robb Walsh and illustrated by David Wenzel. Released in 1980, it presents itself as an archaeological and sociological study of the mythical dwarves as they lived and thrived over 1500 years ago. Again, it draws upon popular myth and legend to weave something greater, building upon the fairy tales of old to postulate the dwarves as an entire race of their own. It shows how they could have built an empire underground, and where they came from before then. It links them to any number of stories passed down to our time, including Stonehenge and Camelot.

Lest no underground-dwelling creature of myth be left out, next on the list is Kingdom of the Dwarves, by Robb Walsh and illustrated by David Wenzel. Released in 1980, it presents itself as an archaeological and sociological study of the mythical dwarves as they lived and thrived over 1500 years ago. Again, it draws upon popular myth and legend to weave something greater, building upon the fairy tales of old to postulate the dwarves as an entire race of their own. It shows how they could have built an empire underground, and where they came from before then. It links them to any number of stories passed down to our time, including Stonehenge and Camelot.

The strengths of this book lie in the sharp, fully-realized drawings and occasional colored painting that scatter throughout, illustrating the various aspects of the dwarves’ lives. However, a goodly number of retold legends and stories about the dwarves to further expand upon what we know or think we know also make it an entertaining read.

Kingdom of the Dwarves is interesting, even beautiful in its own right. Postulating them as a highly advanced race which influenced our own development before falling to a catastrophic plague before fleeing or dying is certainly an interesting choice, but no harder to swallow than any of the other theories regarding mythic creatures (such as the one where they’re a third aspect of angels who refused to takes sides and so were cast down to Earth). It’s quirky, and worth checking out if you can track down a copy.

Our next stop as we look at mythic races is a Tolkien-influenced book, The Hobbit Companion, written by David Day and illustrated by Lidia Postman. By now, I’m sure it’s a bit redundant to say that this book is inspired by those odd hairy-footed creatures of comfort that play such a big role in The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. It draws extensively from Tolkien’s many and thorough writings on the history and societies of Middle-Earth, and as far as I can tell, it does a very satisfactory job of making it accessible and welcoming for new and old readers alike. That is, if they like literary games and clever language analysis.

As the book says, it’s “an exploration of the inspirational power of language. It proposes that the entire body of Tolkein’s writing dealing with Hobbits was essentially the product of a list of asssociations with the word Hobbit. Thus, the invention of the word Hobbit resulted in the creation of the character, race, and world of the Hobbit.” That sounds pretty serious to me. Clearly, this book aspires to go above and beyond the call of duty in taking us on a tour of the world of the Hobbit. It certainly takes some interesting side-trips. For instance, the fact that “hobbit” appears right after “hoax” in many dictionaries is significant and worthy of analysis; that the entire Hobbit is presented as a literary hoax rather than a true novel.

There’s an extensive study of the name Bilbo Baggins, and how it relates to the nature of the character and his role in Hobbit society and in the book itself. I never knew you could read so much in to one name. The analysis of Gollum’s name in relationship to goblins, hobbits, hobgoblins, and more is just… uncanny. And it only gets more interesting and convoluted from there as it studies the Shire, Bag End, The Tooks and the Brandybucks, Gandalf, trolls, giants, dragons, rings, thieves, the Fellowship and Frodo. All the while picking apart words and phrases and names, looking for hidden meaning and strange relations that I never would have thought extant. Just as Tolkein was a true scholar of linguistics, so does David Day tease apart the strands of Middle-Earth to spiritedly explain what it all might possibly mean.

This is an amazing book, dizzying in its complexity, but astounding in the way it offers up the information and presents it to be studied, digested, and possibly even understood. While it looks like a rather generic Tolkein-inspired book at first, it swiftly establishes and maintains its own unique identity. This is one for the scholars, trivia experts, and those who love working with words.

Having conducted a tour of the other races, we now circle back around to the beginning, with The Great Encyclopedia of Faeries, written by Pierre Dubois, and illustrated by Claudine and Roland Sabatier. My goodness. This one is really serious about its business, coming across as a weighty tome chuck-full of fairy goodness. Seriously, it collects a whole (shining) host of myths, legends, lore, fairy tales and the like from all across the world to give us a rather thorough collection of fairy-related information.

Having conducted a tour of the other races, we now circle back around to the beginning, with The Great Encyclopedia of Faeries, written by Pierre Dubois, and illustrated by Claudine and Roland Sabatier. My goodness. This one is really serious about its business, coming across as a weighty tome chuck-full of fairy goodness. Seriously, it collects a whole (shining) host of myths, legends, lore, fairy tales and the like from all across the world to give us a rather thorough collection of fairy-related information.

The sections are broken up into “Maidens of Clouds and of Time,” “The Faeries of the Hearth,” “The Golden Queens of the Middle World,” “The Faeries of Rivers and the Sea,” “The Maidens of the Green Kingdom,” and “The Ethereal Ones of Infinite Dreams.” Despite the somewhat flowery nature of these chapter titles, the actual material contained within each chapter is serious, and far-reaching, looking at fairies on a global level. For instance, that first chapter includes the Valkryies, Mother Holle, genies and assorted thunder gods, and even Saint Lucia, Cinderella, and the Sleeping Beauties. Faeries of the Hearth include Melusine and assorted countryside dragons. I’d even go so far as to say that the majority of the fairies and creatures spotlighted in this book are more obscure, lesser-known, and Eurocentric. The entries vary in tone and aspect from creature to creature; each one is detailed with stories and tales, while sidebars contain the bare facts like size, appearance, dress, food, habitat, custom and activities.

Combining this more in-depth look at lesser-known legends and fairy creatures with some stylish, absolutely beautiful artwork, The Great Encyclopedia of Faeries manages to live up to the high ideals set forth by its name. It has enough new or obscure information, and presents it in such an approachable manner, that it’s sure to be a welcome addition to any reference section or bookshelf.

Finally, we end our tour with a collection brought together and adapted by one of Green Man’s favorite experts, Jane Yolen, who gives us The Fairies’ Ring: A Book of Fairy Stories and Poems. She’s joined in this by illustrator Stephen Mackey. Unlike the other books in this review, The Fairies’ Ring is a collection of poetry and stories about the Fae, as opposed to a concordance or encyclopedia. Yolen has brought together both old and new in an effort to best present the full range and scope of the fairies’ nature.

Finally, we end our tour with a collection brought together and adapted by one of Green Man’s favorite experts, Jane Yolen, who gives us The Fairies’ Ring: A Book of Fairy Stories and Poems. She’s joined in this by illustrator Stephen Mackey. Unlike the other books in this review, The Fairies’ Ring is a collection of poetry and stories about the Fae, as opposed to a concordance or encyclopedia. Yolen has brought together both old and new in an effort to best present the full range and scope of the fairies’ nature.

There’s a prose retelling of Thomas the Rhymer, always one of my favorite myths, and a selection from Shakespeare’s Midsummer Night’s Dream. There’s works by William Cory (Catching Fairies), Ben Jonson (Queen Mab), Sir Walter Scott (Fairy Song), W.B. Yeats (The Stolen Child), and several from Yolen herself (The Queen of the Fay, and Where To Find Fairies). Over two dozen in all, ranging from England to Persia, from Scotland to France, from Greece to New Zealand, from Wales to Africa, representing numerous cultures. In some cases, the story remains intact; in others, Yolen has adapted existing tales to better present the proper atmosphere and feel for the fairies.

In every case, Mackey gives us some drop-dead artwork, which captures the feyness of the fairies, injects an ethereal tone into the people, and invokes something rich and wild all the way through. It’s easy to pick out the Faerie Queen in one of his paintings; she’s unmistakable. Landscapes are mysterious, holding that air of enigma and challenge, so that one might truly believe the fairies live just under the hill or around the corner. These paintings are lush, soft in a Victorian manner, romantic without being sensitive. And they tell the story.

Finally, a short essay on source notes explains where each of these stories came from, or where Yolen found her inspiration. It’s very helpful, especially as a springboard towards finding out more.

And that concludes our tour for the time being… make sure you don’t get lost on the way home.

“I have come back from the hidden, silent lands of Faery

And have forgotten the music of its ancient streams:

And now flame and wind and the long, grey, wandering wave

And beauty and peace and sorrow are dreams within dreams.”

– “Dreams Within Dreams” by Fiona Macleod